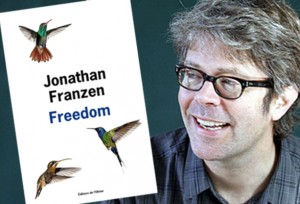

Anyone interested in understanding the subtleties of human identity and love could do worse than read the novels of Jonathan Franzen. He also gave a commencement address at his old college a couple of years ago that struck a powerful chord in our changing times.

He begins by observing how the word ‘sexy’ is ubiquitiously linked to the marketing of any new hi-tech device; the sleek touchscreens, the sensual interface. But the result is that technology itself begins to correspond to ‘our fantasy ideal of an erotic relationship, in which the beloved object asks for nothing and gives everything, instantly, and makes us feel all powerful, and doesn’t throw terrible scenes when it’s replaced by an even sexier object and is consigned to a drawer.’

Life has always been a slow and reflective process with plenty of time to consider who we are and what we want. But the portability of our gadgets means that we fill up all that dead time on the bus, waiting for someone, lying in bed at night by scanning through the our contacts list on our cell phones to count our friends, to check reviews on the cafe we’re currently in, to get attention from strangers on dating sites or update our profile photo to see if anyone will actually notice.

Franzen observes:

‘To speak more generally, the ultimate goal of technology, the telos of techne, is to replace a natural world that’s indifferent to our wishes — a world of hurricanes and hardships and breakable hearts, a world of resistance — with a world so responsive to our wishes as to be, effectively, a mere extension of the self.’

The real message of Franzen’s speech, however, is about the difference between being liked and being loved.

‘A related phenomenon is the transformation, courtesy of Facebook, of the verb “to like” from a state of mind to an action that you perform with your computer mouse, from a feeling to an assertion of consumer choice.

‘But if you consider this in human terms, and you imagine a person defined by a desperation to be liked, what do you see? You see a person without integrity, without a center.’

When we’re desperately in search of an identity then it’s tempting to try to become someone, take a cool new name, wear outlandish clothes and hum mantras on street corners. A downloaded personality is a disposable one, however and ultimately do we need to become someone to be someone?

Franzen summed it up: ‘If you dedicate your existence to being likable, however, and if you adopt whatever cool persona is necessary to make it happen, it suggests that you’ve despaired of being loved for who you really are.’

And when it comes to sharing the details of our day to day lives the sheer banality of people’s updates is sometimes beyond belief. Who really cares what someone else had for breakfast that morning? But as Franzen notes, we’ve become out own paparazzi, our own marketers and consumers of ourselves.

‘Our lives look a lot more interesting when they’re filtered through the sexy Facebook interface. We star in our own movies, we photograph ourselves incessantly.’

Franzen concludes with the message that loving has nothing to do with liking.

‘There is no such thing as a person whose real self you like every particle of. This is why a world of liking is ultimately a lie.’

And:

‘The simple fact of the matter is that trying to be perfectly likable is incompatible with loving relationships. Sooner or later, for example, you’re going to find yourself in a hideous, screaming fight, and you’ll hear coming out of your mouth things that you yourself don’t like at all, things that shatter your self-image as a fair, kind, cool, attractive, in-control, funny, likable person. Something realer than likability has come out in you, and suddenly you’re having an actual life.’

You can hear Franzen’s speech here or read the whole transcript over at the NY Times here.